Feb. 18, 2025

The 29th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP29), held in Azerbaijan from November 11th to 24th, 2024, was the deadline for determining the target amount of climate action funding from developed countries to developing countries for the year 2025 and beyond. However, due to the intensifying conflict between developed and developing countries, negotiations became difficult and the conference was extended. Ultimately, a target was set to implement at least $300 billion annually by 2035, which is three times the current funding target of $100 billion per year (approximately 15 trillion yen).

Regarding the determined funding target, countries like India and island nations are expressing their opposition, stating that it is “too low.” On the other hand, the EU evaluates it as “ambitious and achievable” to triple the target amount. Developing countries, who had mentioned an annual amount of over 1 trillion dollars during the negotiation process, are greatly disappointed, and this could potentially have a negative impact on the future cooperation between developed and developing countries regarding climate change countermeasures.

On the other hand, Hitachi Research Institute considers it commendable that they managed to reach a settlement on the target amount of financial support, for which there had been the possibility of negotiations breaking down, and that they agreed on the detailed rules of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement regarding international carbon credit trading. The achievement rating is 1.8, with a high weight in the field of financial support (Table 1). In addition, in recent years, there has been an increase in the number of voluntary initiatives and pledges announced by willing countries and companies in conjunction with COP meetings, separate from the legally binding COP decisions. COP29 also saw many initiatives and pledges (Table 2).

| Area | Achievement (agreement) | Weight(%) | Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitigation |

|

20 | 2.0 |

| Adaptation |

|

15 | 1.5 |

| Loss and damage |

|

15 | 1.5 |

| Financial support |

|

50 | 2.0 |

| Overall evaluation | 1.8 | ||

| Area | Content | Participating parties |

|---|---|---|

| Storage battery and power grid |

|

45 power companies and suppliers (including Hitachi Energy and Siemens) |

| Coal-fired power plant |

|

EU and 25 countries (Japan and the U.S. are the only G7 countries that have not signed) |

| Tourism |

|

More than 50 countries (names not disclosed) |

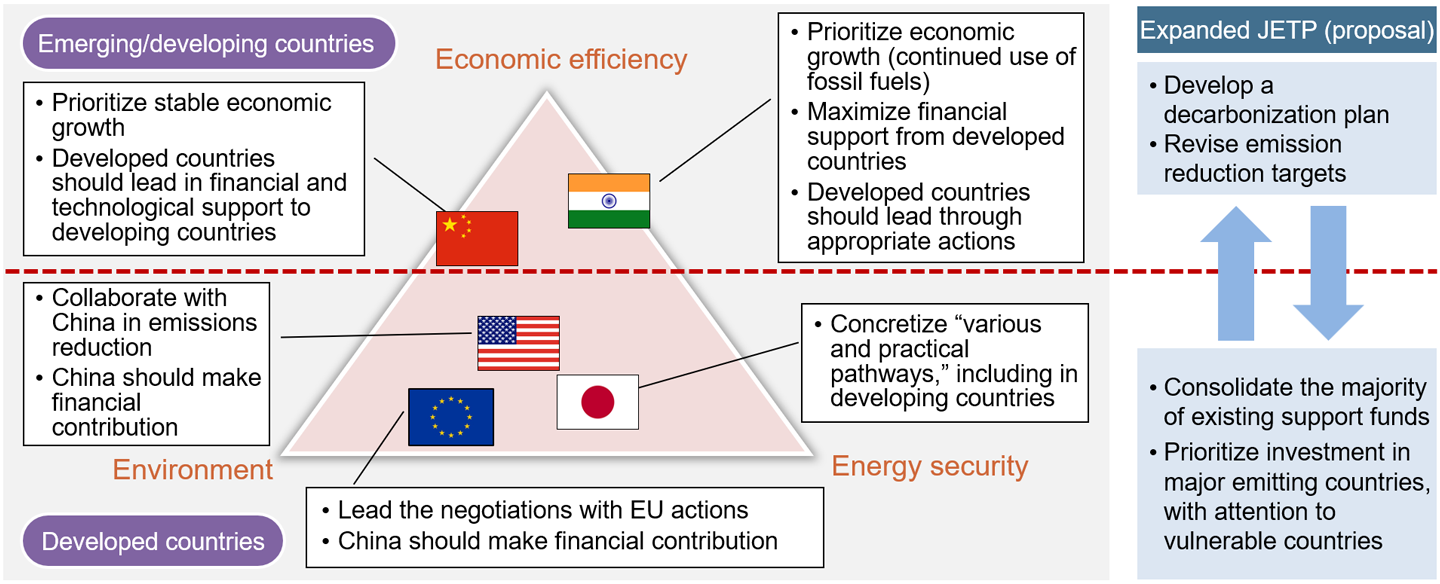

At COP29, each country and region deployed negotiation tactics prioritizing their own interests. However, at the core, it is assumed that there are strategies to plan decarbonization while balancing the 3Es (environment, economic efficiency, and energy security) based on the specific circumstances of each country and region (Figure 1).

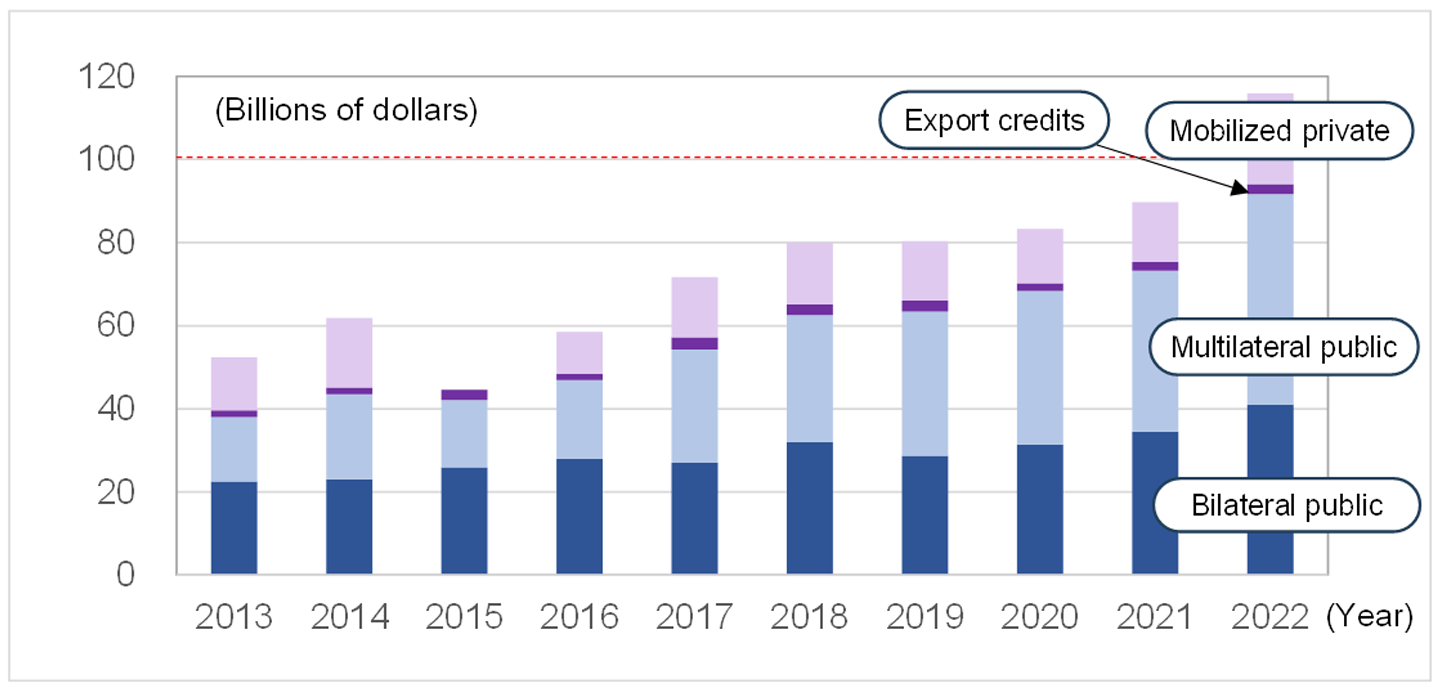

The current funding target of 100 billion dollars per year was originally set for 2020 but was extended to 2025 due to it not being achieved. It was finally achieved in 2022 (Figure 2). Based on this, it can be said that achieving the funding target of 300 billion dollars per year, as decided in COP29, will not be easy.

The discussions leading up to COP29 regarding financial support mainly focused on the scale of funding, with less discussion on the content of financial support. Moving forward, there is room for consideration of proposals from a broader perspective, such as the “Expanded JETP (Just Energy Transition Partnership)” proposed by the European think tank Bruegel, as a feasible plan. The operation of JETP, established in 2021 by a group of developed countries, has begun, and it is currently supporting coal phase-out plans in countries such as South Africa, Indonesia, and Vietnam. It is a scheme that aims to develop ambitious plans for energy transition and provide substantial financial support to achieve them. However, there have been concerns raised about insufficient financial contributions from developed countries to JETP.

Figure 1: View of each country and region and expanded JETP (proposal)

Figure 2: Climate financing support from developed countries to developing countries

On the other hand, there are voices calling for COP reform, as the COP meetings have not been able to achieve the necessary results at a sufficient speed. On November 15th during the COP29 session, 22 environmental experts including Ban Ki-moon, former UN Secretary-General and Johan Rockström, the proponent of “planetary boundaries,” sent an open letter to the Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and others, raising this issue (Table 3). Considering the background leading up to COP29, proposals (1) to (4) can be considered urgent tasks.

| Item | Content |

|---|---|

| (1) Improve the selection process for COP presidencies |

|

| (2) Streamline for speed and scale |

|

| (3) Improve implementation and accountability of national targets |

|

| (4) Ensure robust tracking of climate financing |

|

| (5) Amplify the voice of science |

|

| (6) Recognize the interdependencies between poverty, inequality and environment |

|

| (7) Enhance equitable access |

|

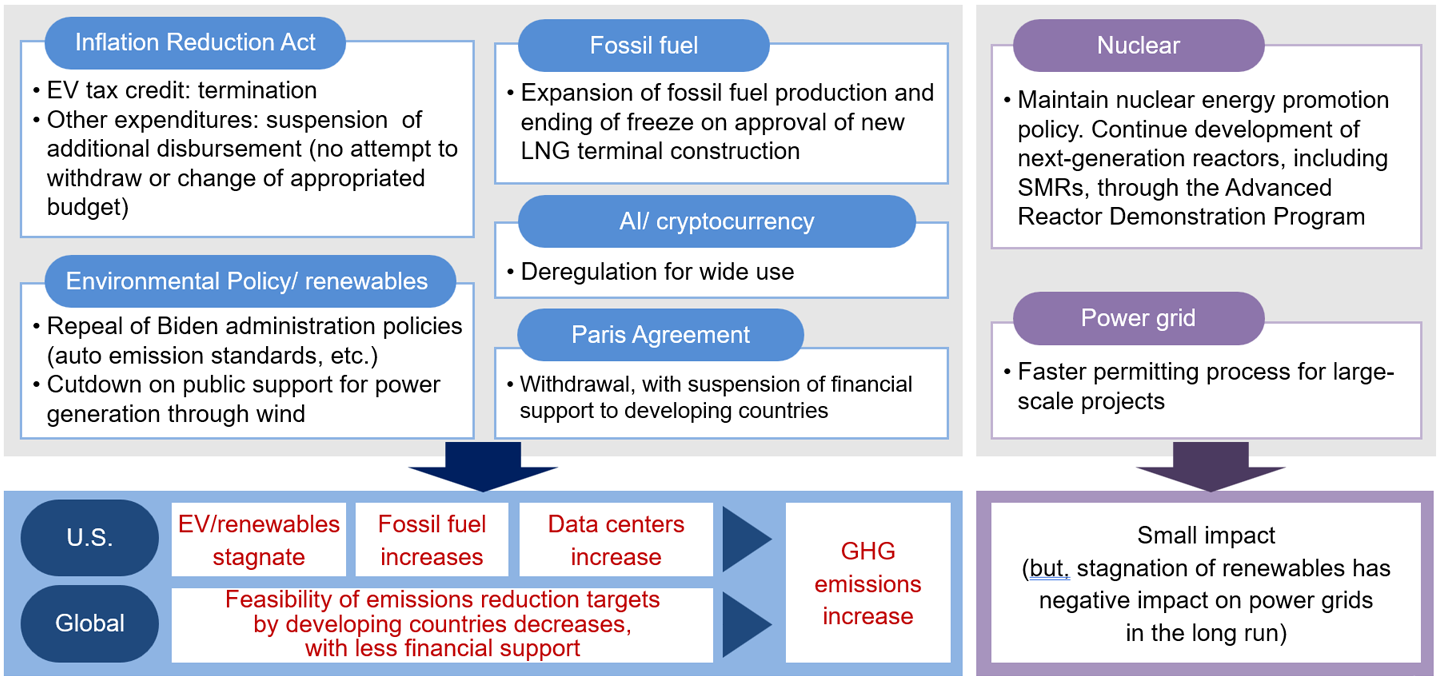

President Trump had promised to review the domestic decarbonization policies and withdraw from the Paris Agreement, and signed the executive orders on these issues on the day of inauguration (Figure 3). Firstly, the review of the decarbonization policies will work in the direction of increasing greenhouse gas emissions in the United States, making it uncertain whether the United States will achieve its 2030 target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50 to 52% (compared to 2005 levels). If the emissions from the second-largest emitter in the world, the United States, start to increase, it will exert upward pressure on global emissions as a whole. Secondly, the amount of financial support from the United States to developing countries will decrease significantly, which will reduce the feasibility of achieving the targets for many developing countries that have set their emission reduction goals based on the assumption of financial support.

Figure 3: Policies of the Trump administration and its impact

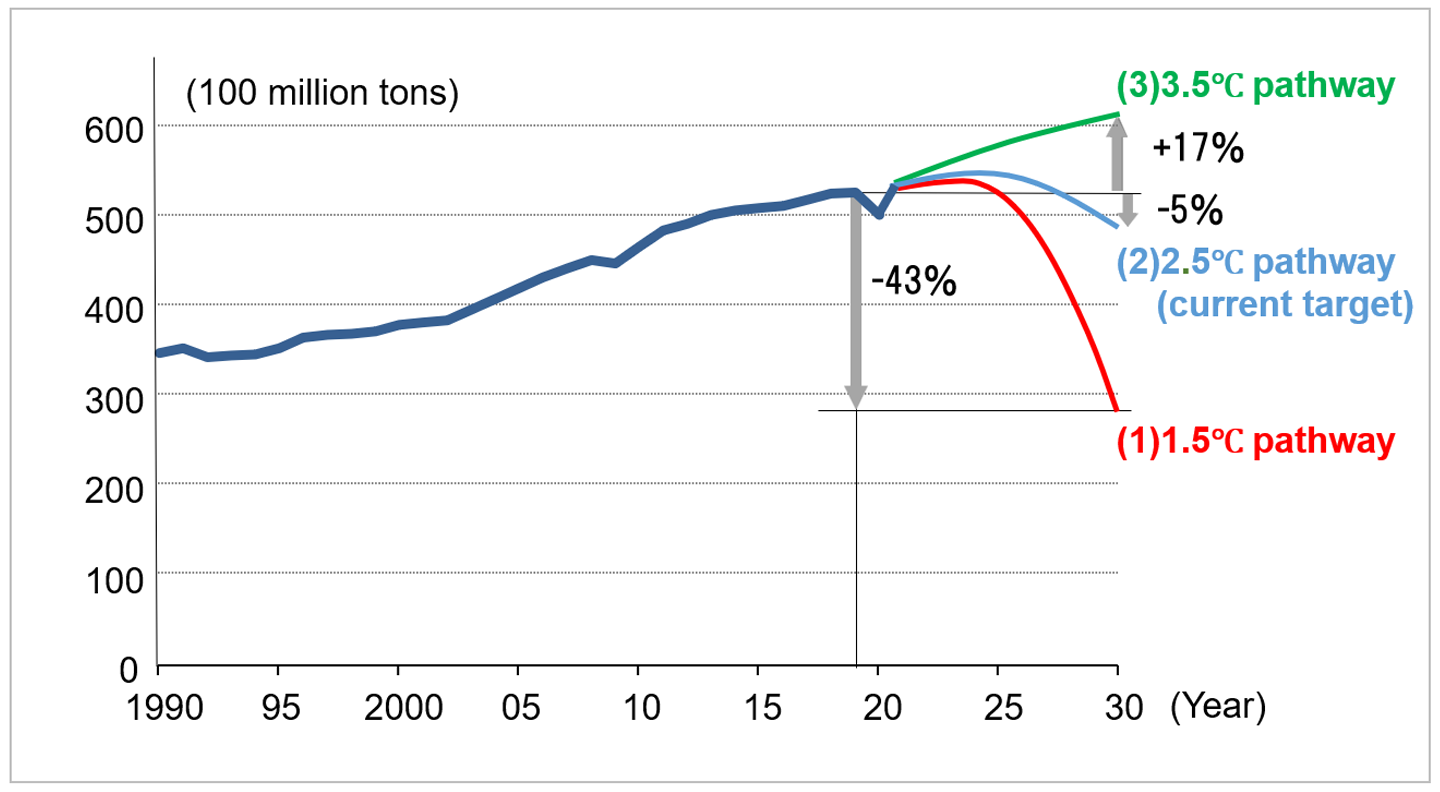

Hitachi Research Institute assumes three cases as pathways for greenhouse gas emissions towards 2030 (Table 4, Figure 4). It is quite difficult to further increase the 2030 emission reduction target to 43% compared to 2019 to achieve the “(1)1.5°C pathway” given the significant gap between the “(1)1.5°C pathway” and the current targets of each country, which are stacked up in the “(2)2.5°C pathway.” Additionally, it is becoming uncertain whether the “(2)2.5°C pathway” can be achieved. As mentioned earlier, with the backtracking of climate change measures in the United States and the possibility of insufficient financial support to developing countries, there is a possibility that the current targets of major emitting countries such as China, the United States, and India, as well as other emerging and developing countries, may not be achieved. Therefore, we set the “(3)3.5°C pathway” as the main case, where the current targets are not achieved. According to a report from the United Nations Environment Programme (dated October 24, 2024), it warns that if current policies are extended in each country, the average global temperature will rise by 3.1℃.

| Case | Greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 | Feasibility(%) | Corresponding scenarios

by other institutions |

Decarbonization market (annual, trillion dollars) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Paris Agreement achieved: 1.5°C pathway |

|

Less than

20 |

IEA Net Zero Scenario (NZE) |

3.5 |

| (2) Paris Agreement not achieved: 2.5°C pathway |

|

30 | IEA Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS) [Announced Pledges Scenario (APS) is also relevant] |

2.8 |

| (3) Current target not achieved: 3.5°C pathway |

|

50 | UNEP Current Policies Scenario |

2.2 |

Figure 4: Historical and future trends in global greenhouse gas emissions

A major milestone after COP29 is COP30 (November 2025, Brazil), where the next round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) for the period until 2035 will be submitted. The deadline for submitting the next NDCs is February 2025, but it is unlikely that developing countries, who are dissatisfied with the target amount of $300 billion in financial support, will submit ambitious reduction targets. As a result, the likelihood of the world as a whole following the pathway to achieve the 1.5°C target of the Paris Agreement (a 60% reduction by 2035 compared to 2019) is low.

Researchers and others have begun to propose revising the normative vision of the 1.5°C target, which is maintained in COP negotiations and policy discussions in various countries. For example, the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Public Policy has listed the following three options as choices for temperature targets. Option 2 is “returning to an achievable temperature target (e.g., a 2°C target) and prioritizing a balance between emission reduction measures and adaptation measures.” It is important to note this possibility they present and there is room for consideration.

⇒Temperature target options (University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Public Policy):

However, amidst the increasing global average temperature and the frequent occurrence of extreme weather events caused by climate change, there is a low possibility of revising the 1.5°C target due to the political intention to maintain momentum in the COP process. Additionally, while COP30, where the discussion on emission reduction targets until 2035 will take place, there is a possibility that the momentum to review the 2030 targets may not increase, raising concerns that global attention will shift from 2030 to 2035.

Naofumi Sakamoto

Senior Strategy Staff, Global Intelligence and Research Office

He is engaged in research on policy and industry trends in the fields of energy and environment.

He joined Hitachi in 1992 and has worked on development of global strategy and service-business strategy before assuming his current position.

Author’s Introduction

Naofumi Sakamoto

Senior Strategy Staff,

Global Intelligence and Research Office

We provide you with the latest information on HRI‘s periodicals, such as our journal and economic forecasts, as well as reports, interviews, columns, and other information based on our research activities.

Hitachi Research Institute welcomes questions, consultations, and inquiries related to articles published in the "Hitachi Souken" Journal through our contact form.