Reports by Guest Contributors

Innovation has long been part of finance: from the invention of new financial instruments such as debt and fractional shares to the digitisation of trading and settlement processes, innovation has allowed people better access to capital and capital to be more efficiently deployed. Each technological leap has created efficiencies but also introduced new risks, overall impacting consumers, the industry, and regulators. This article reflects on the evolution of digital finance innovation in Europe. In the past two decades, digital finance in the continent has undergone a particularly dynamic transformation: so-called FinTech went from being a marginal phenomenon to becoming an integral part of today’s European finance. The article will define and cover three main waves of European FinTech and explain the impact they had on Europe from three perspectives: consumers, the industry, and regulators.

The first wave, emerging around the global financial crisis of 2007–2009, introduced start-up-led innovation in basic services like payments and lending. The second, spanning most of the 2010s, witnessed innovative companies started tackling more complex services, including in asset management and insurance—often with a business-to-business (B2B) model, as well as the entrance of BigTech firms. In the third, current wave integration between incumbents and digital finance players keeps increasing, alongside the evolution of decentralized finance beyond cryptocurrencies and the accelerated deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) across all financial sectors.

The paper will argue that each wave has redrawn the contours of European finance. Consumers gained access to cheaper, more convenient services, though often at the expense of data privacy. Industry incumbents have faced competition but also saw new collaboration opportunities emerge. Importantly, European regulators have gradually shifted from a reactive posture—observing and responding to innovations as they emerged—to a more proactive role in trying to guide technological change or pre-empt risk. But innovation in digital finance continues to move faster than policy frameworks can easily accommodate. The challenge for Europe continues to be enabling innovation while safeguarding the policy goals and principles of financial stability and consumer rights that underpin the trust in its financial industry.

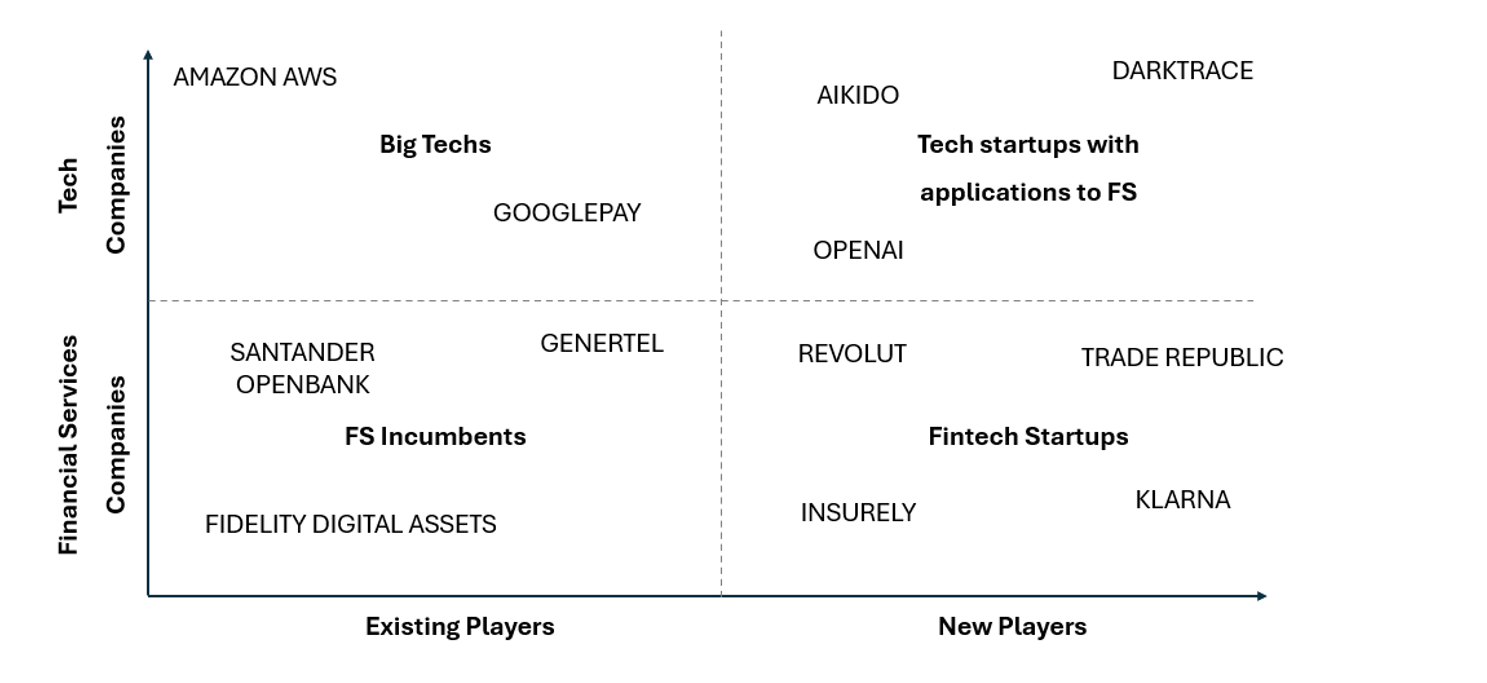

Understanding the evolution of digital finance requires a clear view of the industry and market structures in which financial technologies operate. FinTech startups are only one part of the story. In this paper I propose a simple matrix framework (Figure 1) that identifies four categories of actors, along two dimensions: whether they are incumbent or new entrants, and whether their primary specialization lies in finance or technology. This yields four types of players: traditional financial incumbents such as banks and insurers; specialised FinTech start-ups offering financial services; BigTech firms expanding into finance from adjacent markets; and technology providers (often startups) whose products can support also financial operations.

Each of these actors has different strengths that allow it to compete in this industry. Incumbent financial institutions typically operate diversified business models and benefit from economies of scale in capital deployment and management. In contrast, FinTech start-ups tend to concentrate on single products at first—such as payments, lending, or personal finance management—leveraging advanced technology and lean operations to challenge established firms. BigTech firms enter financial servies often as an extension of their product/service offering, using their large non-financial customer base and their data, integrating financial functions into their broader platforms. Finally, new tech-focused firms—such as those offering AI, analytics or CRMs—benefit from specialization: they aim to be the best at a specific solution, which happens to be used also in financial services—but not only.

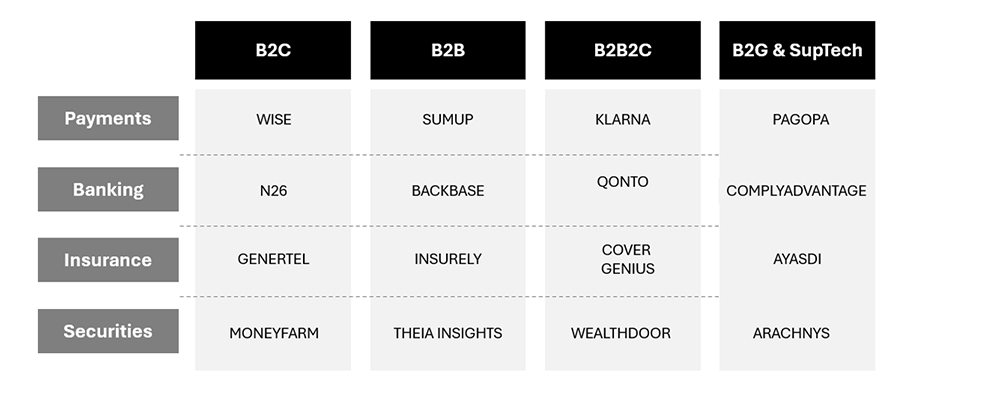

The flip side of this picture is the digital finance market—thinking of firms through the lens of who purchases and uses their products and services. This can also be mapped by intersecting the main segments of financial services (e.g. payments, banking, insurance, securities) and the types of target customer groups—business-to-consumer (B2C), business-to-business (B2B), business-to-business-to-consumer (B2B2C), and business-to-government (B2G), the latter often involving SupTech or RegTech solutions developed for supervisory authorities. Figure 2 shows this and offers some examples of mostly European players for each category. B2C FinTechs offer current accounts or insurance policies directly through apps; B2B players provide white-label digital infrastructure to banks or other financial players; B2B2C models support embedded finance, for instance, where services like credit or payments are integrated into e-commerce platforms; and B2G tools aid supervisors in data analytics and firms in compliance automation.

These two frameworks together show the breadth of actors and business models that digital finance comprises. They provide an orientation tool in a fluid and fast-changing field and can help understand how the industry has evolved in the past two decades.

The first wave of FinTech in Europe emerged in the immediate aftermath of the 2007–2008 global financial crisis. It was characterised by the rise of start-ups targeting the end consumer of financial services, primarily through business-to-consumer (B2C) models. These innovations typically targeted less complex retail financial activities – payments, personal loans, money transfers – which were ripe for digital disruption. Crucially, FinTech startups in this wave sought to exploit areas where incumbent banks were weakest (due to high fees, inefficiencies, or post-crisis reputational damage). By leveraging the internet and smartphones, early FinTech firms could offer consumers convenient services at lower cost, while operating with lower overhead than banks.

In payments, for instance, firms such as the UK-based Transferwise (today Wise) and Revolut started offering real-time digital transfers and foreign exchange services with markedly lower fees than banks. Adyen, from the Netherlands, disrupted online payments for merchants. Meanwhile, peer-to-peer lending platforms such as Zopa, Funding Circle, and Auxmoney aimed to bypass intermediaries altogether by directly connecting borrowers with investors. These platforms operated with lighter infrastructures and, in their early stages, outside the full scope of traditional regulatory regimes.

For consumers, this wave meant broader access to basic financial services, often with greater transparency and lower costs. It also signalled a shift in expectations: that financial services could be digital-first and user-centric. For the financial industry, however, these developments posed an early competitive threat, particularly in highly profitable business lines that had previously been shielded by high entry costs or regulatory hurdles.

From a regulatory perspective, this first wave constituted a first encounter with technology-driven financial firms operating at the edge of existing frameworks. The European regulators response was cautious, largely extending existing rules where feasible—such as incorporating new payment firms under the first Payment Services Directive—but avoiding a comprehensive overhaul. The new FinTechs were typically small enough that they did not pose systemic risks (FSB 2019), so the regulators—busy with stabilizing banks and overhauling prudential rules post Financial Crisis—focused more on consumer and investor protection (making sure, for instance, that P2P lenders had clear disclosures and that payment firms safeguarded customer funds). In summary, the first FinTech wave introduced European regulators to a new class of non-bank financial intermediaries, prompting the first adaptations in oversight approaches, mostly to ensure that innovation occur within an appropriate risk-management framework.

These early disruptions were notable but, due to limited product reach, they left untouched many of the most core activities within financial services—something that would change in the second wave.

The second wave of FinTech had its course in Europe during the 2010s and marked a shift from disruption to integration. Unlike the first wave, dominated by B2C startups often focused on single-feature products, this phase saw FinTech firms increasingly adopting business-to-business (B2B) and hybrid models, or offering a complete suite of services. On the one hand, partly because of the emerging challenges with pure B2C models in such a sticky industry as finance, and partly because of the growing interest on the part of incumbents, FinTechs began supplying technology to traditional finance (TradFi) rather than solely competing with it. On the other, a notable development was the rise of neobanks and digital challenger banks (such as Revolut, N26, Monzo, etc. in Europe) which attracted millions of users by offering comprehensive app-based banking with low fees and modern UX.

This period also brought diversification in technological applications. The convenience of accessing financial services “anywhere, anytime” via smartphones and web platforms was a defining consumer benefit of this wave. Beyond payments and lending, FinTech innovations expanded into complex areas such as wealth management—through automated investment platforms and robo-advisors such as Nutmeg and MoneyFarm—and insurance (e.g., WeFox in Germany, Alan in France), via digital distribution and data-driven underwriting.

Three other underlying phenomena characterized this period. First, distributed ledger technology introduced a new paradigm, albeit for the time being still mostly limited to cryptocurrencies and disconnected from the mainstream industry. For instance, crypto exchange Bitpanda became Austria’s first “unicorn” and Ledger in France was another notable European player.

Second, the relationship between incumbents and FinTech startups evolved through the so-called open banking paradigm. Fintech startups began leveraging the deposit and payment data held by incumbent banks, either through screen scraping technologies or via Application Programming Interfaces (API), to provide additional services such as Personal Finance Management (PFM). Open banking gave rise to a whole ecosystem of service providers (e.g., Solarisbank, Pleo, Raisin) but also FinTechs focused on data and API management (e.g., Tink, from Sweden; Truelayer in the UK). In Europe this trend was meant to be facilitated by the 2015 Payment Systems Directives 2 (PSD2). This obliged banks to open data APIs to enable properly authorised third-party providers to access the data, fostering integrated payment, credit, and personal finance services.

Third, with the entrance of BigTech firms into financial services, large digital platforms with existing customer bases and technological capabilities began offering payments, credit, and more (Apple and Google launched their wallets, Amazon loans to small businesses, and Meta even attempted to launch its own currency). Although these providers were not European, they affected also European markets. They introduced both new competition for incumbents and a new challenge for regulators and supervisors, especially in relation to data privacy and the potential misuse of personal financial data for targeted advertising or anti-competitive practices (Crisanto et al., 2021). Regulators and supervisors responded by broadening their focus from entity-based oversight to a functional on, developing a “same risk; same rules” approach. Yet, the limitations of existing financial regulation in addressing cross-sectoral issues such as data usage, cross-sector competition, and governance of platform models became increasingly apparent.

All in all, the second wave’s impact was a mix of competitive pressure and growing integration, resulting in a more technologically advanced financial sector and more conscious regulatory scrutiny by the end of the decade.

By the end of the 2010s, digital finance had become integral to the delivery of core financial services. This laid the ground for the current wave, in which integration deepens and AI, embedded and decentralised finance push the boundaries of both innovation and regulatory adaptation. FinTech is no longer confined to start-ups; many incumbents have incorporated FinTech capabilities through partnerships, acquisitions (e.g., Holvi and Madiva by BBVA, Compte Nickel and Gambit by PNB Paribas, TradePlus by Credit Suisse), or in-house development. Similarly, FinTechs increasingly operate within regulatory frameworks, blurring earlier distinctions between disruptors and incumbents. “Digital” is evolving ever more from a channel or a wrapper for traditional financial products into a native component of new products and services.

In this period three core innovations are affecting the European industry more structurally. First, distributed ledger technologies (DLTs) and decentralised finance (DeFi) have extended beyond the niche of cryptocurrencies, to include stablecoins, decentralised exchanges, and automated lending platforms (e.g., Aave), which have more overlaps and interconnections with the traditional financial system. While their market footprint remains limited relative to traditional finance, their potential to bypass regulated intermediaries has prompted European regulators to devise dedicated and arguably pre-emptive regulation (e.g., the Market in Crypto-Assets regulation, MICAR; see Guedel and Sciascia 2023). Most notably, the European Central Bank has embarked on an ambitious project to launch a “digital Euro”—a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) that aims to be both a shield against future attempts to replace fiat money by private providers, and an alternative to the established foreign payment networks (especially Visa and Mastercards) (Giani 2025).*1

A second structural shift Involves the systematized sharing of customer data between incumbent financial players and FinTech providers, as well as the embedding of financial services into non-financial platforms. Although PSD2 was implemented very heterogeneously, the trend has continued and evolved into the concept of embedded finance models—data-sharing that allows non-financial firms to offer financial products directly (Dinckol et al, 2023). One notable example are Buy-Now-Pay-Later companies, such as Klarna (from Sweden) and Scalapay (from Italy). Such business models further dilute the boundaries of financial service provision.

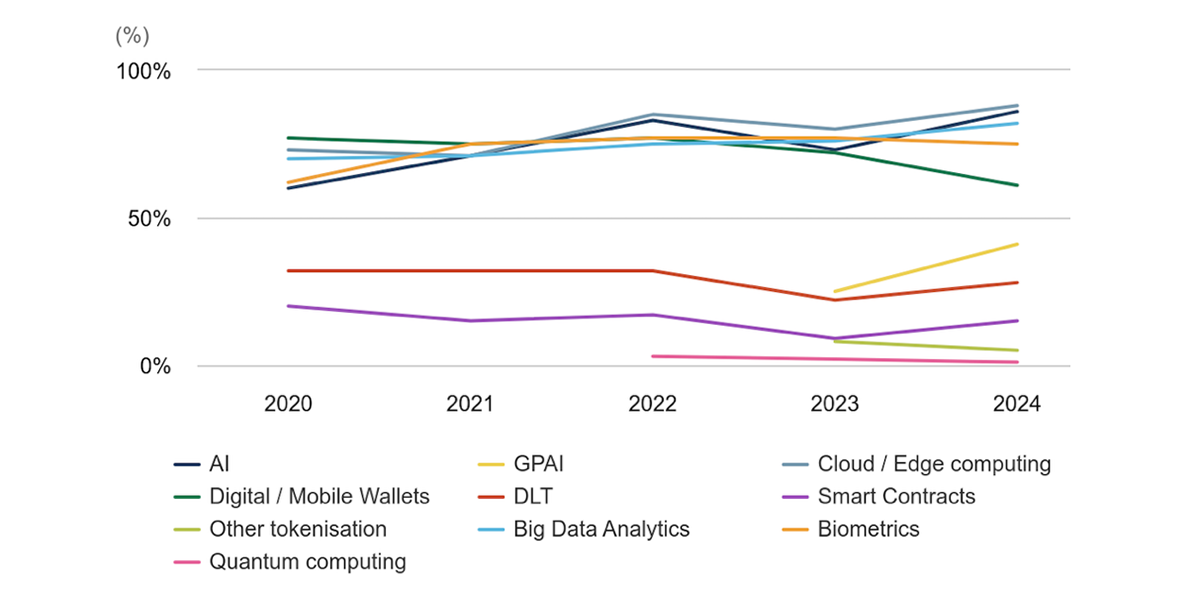

The acceleration of AI adoption marks a third defining feature of this wave. AI is Increasingly used across the financial value chain, from customer service automation to fraud detection, to credit scoring and insurance pricing, to portfolio management. Solutions are both developed internally and sourced from a new generation of AI-native startups (e.g., Veriff, ComplyAdvantage, Tractable, Quantexa).

The next section will expand on the current state of AI in European finance, but it is first worth pointing out that this third wave also involved a notable shift in the European policy response. The EU has clearly shifted towards a more proactive regulatory posture, embodied by the Digital Finance Strategy, and exemplified by regulations such as the MiCA mentioned earlier, and the AI Act. These aim to define the contours and principles of doing finance through innovative technologies, with the goal of providing regulatory certainty and levelling the playing field. At the same time, supervisors have realized that they cannot anymore oversee a technological evolution without being part of it. Supervisory and regulatory bodies have thus likewise begun to adopt SupTech and RegTech tools for surveillance, reporting, and risk detection (Prenio, 2024; Cambridge SupTech Lab, 2023).

With large volumes of structured data and data-driven processes, finance was well placed to embrace artificial intelligence. Firms now increasingly embed it across the sector, especially for operational efficiency and client-facing functions (OECD, 2023a and OECD, 2023b; Aldasoro et al. 2024).

In credit and risk management, AI can improve scoring by identifying non-linear patterns in large datasets and incorporating alternative data—such as transaction histories or online behaviour (Hadji Misheva 2025). Fraud detection and anti-money laundering systems increasingly rely on pattern-recognition algorithms to monitor high-volume transactions in real time. Next-generation onboarding tools now automate identity verification and document analysis, reducing costs and processing time (Hadji Misheva 2025). AI also has clear applications in asset management—for portfolio optimisation, sentiment analysis, and algorithmic trading—and insurance, where claims assessment and pricing have been using it for some time. Across the sector, chatbots are then increasingly dominating the front-end for customer support (Hadji Misheva, 2025).

The applications however come with material risks. European Supervisory Agencies have identified three main concerns of the use of AI in finance. First, bias in decision-making algorithms can replicate or amplify discriminatory outcomes, particularly in credit scoring and insurance pricing, which is especially problematic if compounded by opacity and weaknesses in privacy and data governance (Orwat 2020; Lamb, P., & Arevalo, J. 2025; Giudici et al. 2019). Although the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provides useful guardrails, inadequate protection or misuse of AI may subtly breach GDPR standards and undermine trust. Second, concentration of AI providers and herding effects can threaten the industry resilience and amplify volatility, with risks for financial stability (Guagliano and Mejdahl, 2025; ESMA TVR 2024 and 2025; FSB 2017). Finally, AI introduces cyber risks such as “data poisoning” and AI-generated fraud, prompting calls for continuous monitoring and adaptive policy tools (Guagliano and Mejdahl, 2025).

So, in this context, how is Europe’s financial industry using AI? The next section examines how different segments of European financial services are adopting this technology and managing these risks in practice.

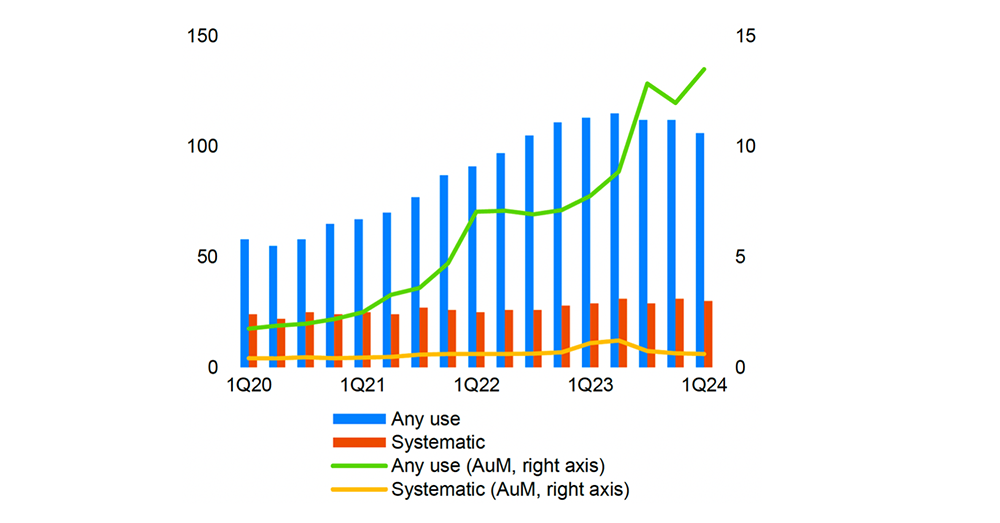

AI adoption across the European financial sector has accelerated, though patterns vary by sub-sector. In asset management, uptake remains limited to non-core functions. As of early 2024, only 145 EU investment funds explicitly disclosed AI or machine learning use in their strategy, representing just 0.1% of total assets under management (ESMA 2025). These are typically systematic funds applying machine learning to quantitative models. Interestingly, data shows that their performance has not consistently outpaced traditional funds, and investor flows have been volatile (ESMA 2025). In this segment, however, exposure to AI is also indirect, via investments in AI-linked companies. From 2021 to 2024, European equity funds increased their holdings in AI-related firms from 8% to 12.5% by weight, reflecting broader market enthusiasm and indices’ composition (ESMA 2025). While not itself evidence of AI use, this trend represents an AI-related risk: thematic concentration and vulnerability to valuation corrections.

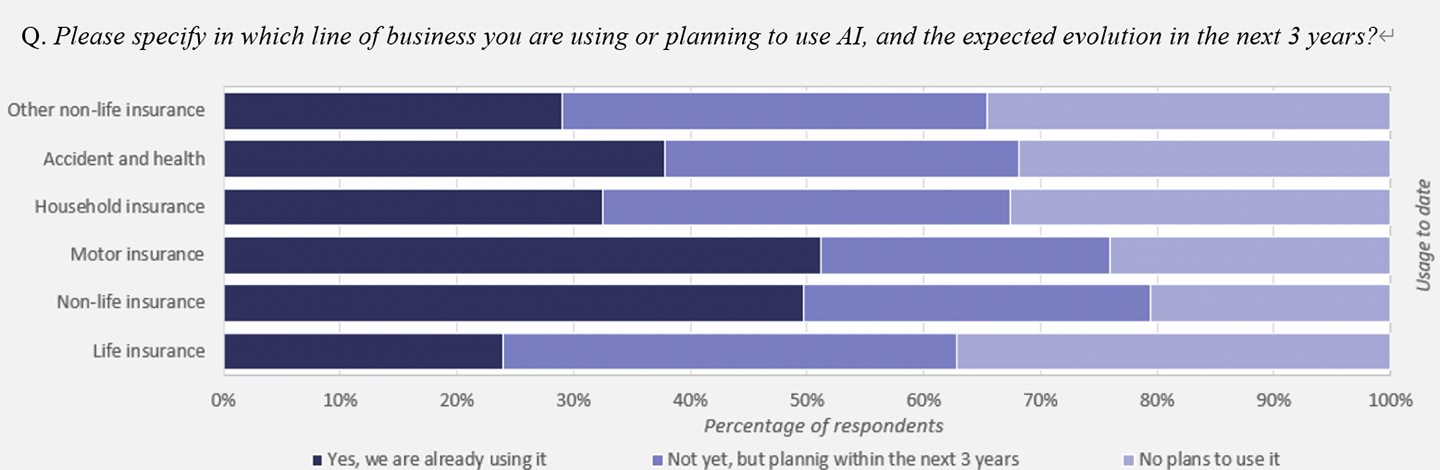

In the insurance sector, adoption is more widespread. A 2023 European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Agency (EIOPA) survey found that 50% of non-life insurers and 24% of life insurers in the EU were already using AI, with over 30% planning to implement AI tools within three years (EIOPA 2024). Common use cases include pricing, claims management, and customer service—particularly chatbots, which were cited as the most deployed AI application. Most insurers adopt a “human-in-the-loop” approach, with AI systems providing recommendations that are subject to human review (EIOPA 2024).

Despite the adoption, this does not appear to be a coordinated strategy. Only 24% of surveyed insurers had a dedicated AI strategy, though 84% incorporated AI within broader IT strategies. As expected, most of this adoption is also through third-party providers: about 80% relied on external providers for AI-related technology, raising concerns about third-party dependency. In particular, if these providers are foreign, it might that as the industry become more AI-driven, it also becomes less European-powered.

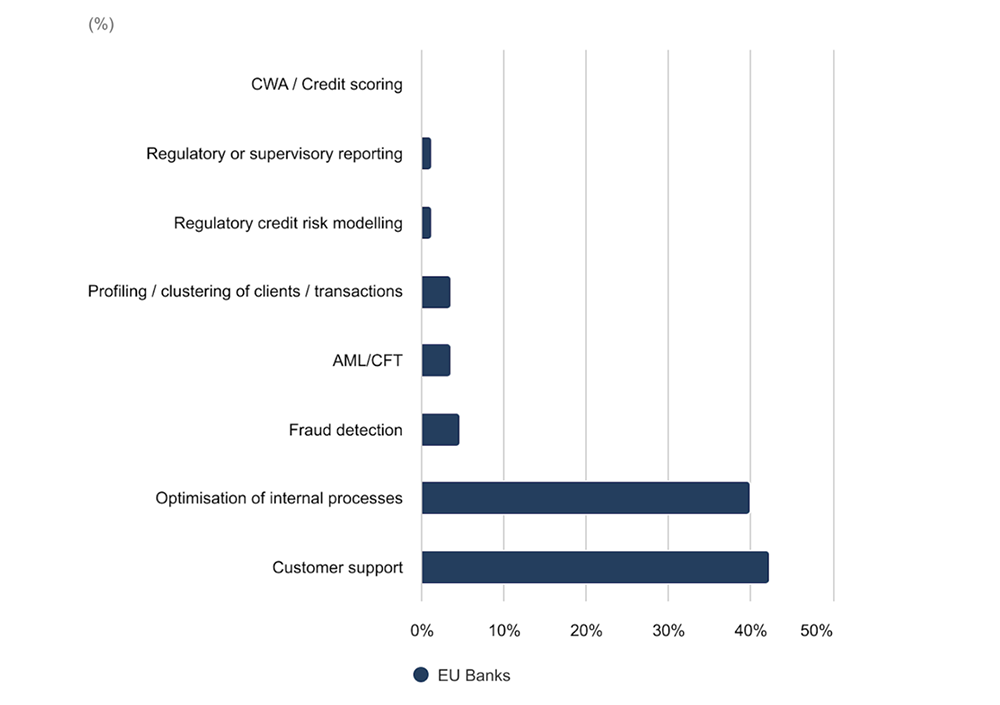

In banking, AI adoption is expanding but remains more cautious in high-stakes domains. A 2024 European Banking Authority (EBA) survey identified common use cases such as customer segmentation, fraud detection, AML monitoring, and credit scoring (EBA RAR 2024). In credit assessment specifically, banks tend to favour simpler, more interpretable models: 59% reported using regression-based methods, 45% used decision trees or random forests, while only 17% employed neural networks (EBA RAQ Spring 2024).*3 These figures suggest that although AI is being integrated into operational workflows, most institutions are avoiding more opaque or experimental techniques in core risk functions. Interest in generative AI is growing: 40% of European banks were using GenAI tools in 2024, primarily for customer support and internal document processing. Nonetheless, large-scale deployment beyond these remains limited, and concerns around model reliability, explainability, and data privacy continue to constrain more ambitious use cases (EBA RAR 2024).

All in all, AI adoption in European finance is expanding but remains uneven. In the meantime, Europe’s regulators have taken a stance, with a regulation that identifies the riskiest uses of this technology—including in finance—and sets out the requirements companies will have to follow to operate safely.

As explored in previous sections, the adoption of AI across financial services—whether in credit scoring, insurance pricing, or portfolio optimisation—has prompted concerns around bias, opacity, and systemic risk. The EU decided to take a proactive approach to limiting these risks, through its Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), adopted in 2024. The Act seeks to govern AI across all sectors, including finance, through a single horizontal framework grounded in risk classification (Almada 2025).

The Act defines four risk categories: unacceptable, high, limited, and minimal. Unacceptable-risk applications—such as certain biometric surveillance tools or social scoring—are banned outright. High-risk systems, which explicitly include AI used for creditworthiness assessment and life or health insurance pricing, are permitted but subject to strict mandatory requirements. These include robust documentation, human oversight, data quality controls, and post-deployment monitoring. Limited-risk systems must provide basic transparency, while minimal-risk AI (e.g., spam filters) remains largely unregulated (EU AI Act).

Although the Act entered into force in August 2024, most obligations on high-risk systems were meant to become enforceable by mid-2026 (and may be postponed), giving firms and supervisors a transitional window for implementation.*4 For financial institutions, this implies that any AI system affecting consumer access to credit or insurance must be reviewed for compliance not only with financial regulation (e.g., MiFID II, Solvency II), but also with the Act’s horizontal standards. In Europe, thus, the financial sector faces an increasingly layered compliance landscape, which raises challenges but also strengthens accountability.

The AI Act’s proactive stance is thus the ultimate example of the broader European regulatory trend recounted in this paper: the shift from reactive to proactive regulation. Even more so than other pieces of regulation such as the Digital Operational Resilience Act and the Markets in Crypto-assets Regulation, the AI Act aims to shape the conditions for innovation development, rather than merely respond to its adoption. The ambition is to offer legal certainty, increase consumer safeguards, and ensuring a level playing field for firms operating across the Union. More broadly, Europe aimed to be a trailblazer in this field, consolidating its credibility as a rule-maker in global digital governance (The Economist, 20 August 2024), through an expansion of what has been called the “Brussels effect” (Bradford 2020).

Yet, technology moves fast and critics warn that a static legal framework may quickly become outdated as AI evolves.*5 General-purpose and generative models, in particular, may not align neatly with predefined risk categories. Concerns also abound about compliance burdens and potential disincentives for innovation, especially for smaller providers (Espinoza et al. 2023; Almada and Radu 2024). It is yet to be seen whether the AI Act will prove to be an enabler of better innovation or too tight a constraint for European companies to compete in the global AI race.

In the past two decades digital finance—from early FinTech disruptions to AI-enabled transformation—has changed the face of European financial services in Europe.

This paper has proposed to think of three main waves to understand the changes that FinTech has brought to the industry. Each has introduced new ways of accessing financial services for consumers, challenged the incumbents, but also tested the boundaries of existing regulations and supervisory capacity. Over time, the EU’s response has shifted from a reactive posture to a more proactive approach, using regulation to both promote innovation and pre-empt risks. The AI Act embodies this stance.

So, what will the next wave of digital finance bring, and is Europe fit for it? The European financial system’s resilience and progress will depend on how well industry and regulators can continue to adapt. The experience so far is encouraging; Europe has fostered a vibrant FinTech sector (including global leaders), while also pioneering regulation that has influence beyond the continent. As we move deeper into the age of AI and digital finance, Europe’s emphasis on strong consumer protection and ethical tech use, if well-reflected in regulatory and supervisory approaches, could be a strength. Finance is fundamentally about trust, and maintaining that trust in a digital, automated, and decentralized context is the next great challenge. But technology moves quickly and, in the context of greater emphasis on technological strategic autonomy, Europe cannot afford to be just a well-regulated market for foreign technologies. It must continue to find a balance that allows it to continue to be at the forefront of digital finance also in the era of AI.

Lorenzo Moretti

Research Fellow, Florence School of Banking and Finance, European University

Lorenzo Moretti is a Research Fellow at the Florence School of Banking and Finance. He is a public policy expert with a background in government, the private sector, and academia. His expertise spans finance, digitalisation , and innovation policy. Throughout his career, Lorenzo has worked in both private and public financial institutions in the US, the UK, and Italy. In his last role, Lorenzo was policy coordinator for Italy’s Minister of Technological Innovation and Digital Transition during Mario Draghi’s government. He is a regular commentator on Italian economic and innovation policy. His analyses have appeared in various Italian and European media outlets. He holds a degree from Brown University in economics and political science and a PhD from the University of Oxford on government venture capital in Europe.

Aldasoro, I., Gambacorta, L., Korinek, A., Shree, V., & Stein, M. (2024). Intelligent financial system: How AI is transforming finance (BIS Working Paper No. 1194). Bank for International Settlements.

Almada, M. (2025). The EU AI Act: Logic, content, and implications for finance (pp. 103–112). In L. Moretti, L. Rinaldi, & P. Schlosser (Eds.), Digital finance in the EU: Navigating new technological trends and the AI revolution. European University Institute.

Almada, M., & Radu, A. (2024). The Brussels side-effect: How the AI Act can reduce the global reach of EU policy. German Law Journal, 25(4), 646–663. https://doi.org/10.1017/glj.2023.108

BEUC — The European Consumer Organisation. (2020). Artificial intelligence: What consumers say: Findings and policy recommendations of a multi-country survey on AI.

Beerman, K., Prenio, J., & Zamil, R. (2021). SupTech tools for prudential supervision and their use during the pandemic (FSI Insights No. 37). Bank for International Settlements.

Bradford, A. (2020). The Brussels effect: How the European Union rules the world. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190088583.001.0001

Cambridge SupTech Lab. (2023). State of SupTech Report 2023. University of Cambridge, CCAF.

Crisanto, J. C., Ehrentraud, J., & Fabian, M. (2021). Big Techs in finance: Regulatory approaches and policy options (FSI Briefs No. 12). Bank for International Settlements.

Dinçkol, D., Ozcan, P., & Zachariadis, M. (2023). Regulatory standards and consequences for industry architecture: The case of UK open banking. Research Policy, 52(6).

DNB (De Nederlandsche Bank) & AFM (Authority for the Financial Markets). (2024). The impact of AI on the financial sector and supervision.

Espinoza, J., Criddle, C., & Liu, Q. (2023, September 13). The global race to set the rules for AI. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/59b9ef36-771f-4f91-89d1-ef89f4a2ec4e

European Central Bank. (2024). First progress report on the digital euro preparation phase. European Central Bank.

European Commission. (2020a). A European strategy for data (COM(2020) 66 final).

European Commission. (2020b). Digital finance strategy for the EU (COM(2020) 591 final).

European Commission. (2020c). Retail payments strategy for the EU (COM(2020) 592 final).

European Commission. (2023a). Proposal for a Regulation on a framework for Financial Data Access (FiDA)(COM(2023) 360 final).

European Commission. (2023b). Proposal for a Directive on payment services and electronic money services in the internal market (COM(2023) 366 final).

European Commission. (2023c). Proposal for a Regulation on payment services in the internal market(COM(2023) 367 final).

European Commission. (2023d). Proposal for a Regulation on the establishment of the digital euro (COM(2023) 369 final).

European Commission, DG FISMA. (2024). Targeted consultation on artificial intelligence in the financial sector.

European Parliamentary Research Service (Hallak, I.). (2024). Digital finance legislation: Overview and state of play (PE 762.308).

European Securities and Markets Authority. (2023, February 1). Artificial intelligence in EU securities markets (TRV Risk Analysis, ESMA50-164-6247).

European Securities and Markets Authority. (2024, May 30). Public statement on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the provision of retail investment services.

European Union. (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (General Data Protection Regulation).

European Union. (2022a). Regulation (EU) 2022/868 (Data Governance Act).

European Union. (2022b). Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 (Digital Markets Act).

European Union. (2022c). Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 (Digital Services Act).

European Union. (2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/2854 (Data Act).

European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (AI Act).

Financial Stability Board. (2017). Artificial intelligence and machine learning in financial services.

Financial Stability Board. (2019). FinTech and market structure in financial services: Market developments and potential financial stability implications.

Financial Stability Board. (2021). FSB financial stability surveillance framework.

Financial Stability Board. (2023). Enhancing third-party risk management and oversight.

Giudici, P., & Raffinetti, E. (2023). SAFE artificial intelligence in finance. Finance Research Letters, 56.

Guagliano, C., & Mejdahl, V. (2025). Artificial intelligence in the financial sector: Risks to financial stability (pp. 63–75). In L. Moretti, L. Rinaldi, & P. Schlosser (Eds.), Digital finance in the EU: Navigating new technological trends and the AI revolution. European University Institute.

Hadji Misheva, B. (2025). The potential of AI in traditional finance (pp. 51–62). In L. Moretti, L. Rinaldi, & P. Schlosser (Eds.), Digital finance in the EU: Navigating new technological trends and the AI revolution. European University Institute.

International Monetary Fund. (2024). Global Financial Stability Report: Steadying the course—Uncertainty, artificial intelligence, and financial stability (October 2024). International Monetary Fund.

Kiuhan-Vásquez, S. (2025). Transforming financial supervision with AI: Insights from the EU (pp. 87–94). In L. Moretti, L. Rinaldi, & P. Schlosser (Eds.), Digital finance in the EU: Navigating new technological trends and the AI revolution. European University Institute.

Lamb, P., & Arevalo, J. (2025). Ethical and consumer protection considerations (pp. 113–118). In L. Moretti, L. Rinaldi, & P. Schlosser (Eds.), Digital finance in the EU: Navigating new technological trends and the AI revolution. European University Institute.

Munn, L. (2023). The uselessness of AI ethics. AI and Ethics, 3, 869–877.

Nassr, I. K. (2025). The global artificial intelligence regulatory landscape (pp. 95–102). In L. Moretti, L. Rinaldi, & P. Schlosser (Eds.), Digital finance in the EU: Navigating new technological trends and the AI revolution. European University Institute.

OECD. (2023a). Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Big Data in Finance. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2023b). Generative Artificial Intelligence in Finance. OECD Publishing.

Orwat, C. (2020). Risks of discrimination through the use of algorithms. Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency (Germany).

Prenio, J. (2024). Peering through the hype—Assessing SupTech tools’ transition from experimentation to supervision (FSI Insights No. 58). Bank for International Settlements.

The Economist. (2024, August 20). AI needs regulation, but what kind, and how much? The Economist. https://www.economist.com/schools-brief/2024/08/20/ai-needs-regulation-but-what-kind-and-how-much

Wall, L. D. (2018). Some financial regulatory implications of artificial intelligence. Journal of Economics and Business, 100, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2018.05.003

Author’s Introduction

Lorenzo Moretti

Research Fellow, Florence School of Banking and Finance, European University

We provide you with the latest information on HRI‘s periodicals, such as our journal and economic forecasts, as well as reports, interviews, columns, and other information based on our research activities.

Hitachi Research Institute welcomes questions, consultations, and inquiries related to articles published in the "Hitachi Souken" Journal through our contact form.